Severe Weather Preparedness: How to Keep Your Community Safe When Seconds Matter

Severe weather events and natural disasters, such as hurricanes, tornadoes, severe storms, wildfires and droughts, are wreaking havoc across every part of the U.S. They are happening more frequently, causing tremendous amounts of damage — often in the billions — for each event. So how do you keep your community safe when seconds matter? It starts with severe weather preparedness and understanding the nature and frequency of events impacting your community.

Frequency of Extreme Weather Events is Growing

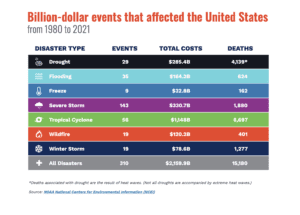

The U.S. has sustained 310 weather and natural disasters between 1980 and 2021, and each event reached or surpassed $1 billion, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI). During this 41-year period, the country experienced an increased frequency of extreme weather events including: 143 severe storms, 56 tropical cyclones, 35 floods, 29 droughts, 19 wildfires, 19 winter storms and 9 freezes. The total cost of all these events is about $2.2 trillion.

The number of major weather or natural disaster events is also increasing in frequency. Before 2014, the U.S. experienced an average of six events annually, but the number has jumped to about 17 per year over the last five years.

2021 Was a Stormy Year

As for 2021, there was 20 severe weather and natural disaster events, according to NCEI. These events include 11 severe storms and four tropical cyclones, as well as wildfires and a drought. They resulted in the deaths of 688 people.

The amount of tornadoes was above average in the lower 48 states, with a total of 1,376 reported. About 100 tornadoes, including an EF-4, moved across the South in March. The year ended with rare, historic tornadoes. Over 90 people died December 10–11 when severe weather produced 68 tornadoes, including numerous EF-4s, which swept across Arkansas, Kentucky, Missouri and Tennessee. One tornado was on the ground for about 166 miles — the longest-track tornado on record in December. Days later, a derecho and a tornado outbreak caused widespread damage in Iowa, Kansas, Minnesota, Nebraska and Wisconsin. More than 60 tornadoes touched down in the region. All told, 193 tornadoes were confirmed in December — the greatest number ever recorded during the month.

Hurricane Ida, which struck Louisiana in late August, caused about $75 billion in damage and was the costliest event in 2021. The Category 4 hurricane made landfall with maximum sustained winds of 150 mph. The energy infrastructure sustained heavy damage, causing widespread power outages for more than 1 million residents in Louisiana.

Planning for the Unpredictable: the Path of Nature’s Fury

Even though each region of the country experiences a different combination of weather and natural disasters, every state has experienced at least one billion-dollar disaster since 1980. The NCEI reported the Central, South and Southeast regions generally have more billion-dollar disasters than other regions. Texas alone has had more than 100 of these events since 1980.

Certain parts of the country are more prone to different types of weather and natural disasters, such as hurricanes, winter storms and wildfires. Inland floods, not caused by tropical cyclones, typically happen in states near large rivers or the Gulf of Mexico and are fueled by rainstorms. Meanwhile, winter storms typically impact the Northeast and Midwest. Hurricanes and tropical storms may strike from Texas to New England, though can impact many inland states with the after-effects of rain and wind. Severe local storms frequently strike across the Plains, Southeast and Ohio River Valley.

Earthquakes generally take place on the West Coast, but major fault lines also exist in the central and eastern part of the U.S. A 2011 earthquake in Virginia, measuring a magnitude of 5.8, was the largest ever recorded on the eastern seaboard.

Wildfires occur in several Southeastern states, including Florida, Georgia and Tennessee, but they’re most common in the West — Montana, Idaho, Wyoming, Colorado, Oregon and California.

Over 7.1 million burned across the western U.S. Large wildfires included the Dixie Fire, which was California’s second-largest fire in history and consumed almost 964,000 acres. The Marshall Fire in Colorado’s Boulder County destroyed over 1,000 homes and businesses, becoming the most destructive fire in state history. At one point during 2021, smoke from the western fires spread across the country and degraded air quality in the Mid-Atlantic and Northeast.

Severe Weather Preparedness Means Being Ready in a Moment’s Notice

Timing to notify and protect communities about severe weather and natural disasters is critical. In some cases, hurricanes, blizzards, extreme temperatures and other events can be predicted and emergency personnel can issue alerts and directions to community members as the situation evolves. For example, hurricane warnings are issued 36 hours in advance of the expected onset of tropical storm winds (sustained wind of 39 mph to 73 mph).

But sometimes emergency managers, 9-1-1 teams, first responders and local government officials don’t get enough advance notice when severe weather or a natural disaster will occur.

Some major events, including earthquakes, flash floods, tornadoes and wildfires, have no or very little lead time to warn both community residents and emergency personnel. Flash floods, for example, may happen within a few minutes of intense rains, when a dam or levee fails, or if an ice jam breaks. These floods can bring walls of water from 10’ to 20’ high, and just 2’ of flood water moving at 9’ per second is enough to move 100 lb. rocks.

Tornadoes usually last about 10 minutes, but can last between a few seconds to over an hour. Alerting a community is extremely important beforehand. The NOAA said the current average lead time for a tornado warning is 13 minutes. This means that from the time a warning is issued to the time it’s predicted to hit an area, people have 13 minutes to seek shelter.

Wildfires can start in seconds, traveling up to 6 mph in forests and up to 14 mph in grasslands. They move fast and unpredictably, so residents are encouraged to evacuate before any danger. The Glass Fire, which burned in California’s North Bay area including Napa and Sonoma counties, exploded overnight and flames consumed one acre every five seconds. More than 67,000 acres were burned over four weeks, forcing about 68,000 people to evacuate.

Timely Response Following Severe Weather Emergencies

Emergency managers, 9-1-1 teams, first responders and local government officials need to be ready for severe weather or a natural disaster itself and the aftermath. Having the best tools and a strong communication strategy will ensure emergency managers can initiate their plan when an adverse event strikes, while 9-1-1 teams and first responders will have a better understanding of what’s happening. It will also help them respond to these events effectively and efficiently. Meanwhile, local government officials will also be able to inform and comfort residents as they announce details and actions around these events.

Telecommunicators are handling more calls from mobile devices. They receive about 240 million calls every year and, in some areas, about 80% of those calls are made from wireless devices. And they must answer calls within 10 seconds during peak time or otherwise within 20 seconds, according to the National Emergency Management Association (NEMA).

Telecommunicators collect relevant information, such as the type of the incident, an accurate description of people and places, and what’s currently happening. Compared to someone who calls 9-1-1 from a landline, telecommunicators have to ask mobile callers for their location information (street address, intersection, nearby landmarks or area of the building/home). The call’s signal is from the strongest cell tower, not necessarily the closest. This inadvertently places the caller miles away from where they actually are.

Just having the location speeds up response times and saves lives. Numerous studies say the average response time for police to respond to an emergency is about 11 minutes and emergency medical services (EMS) personnel are on the scene in eight minutes, while the first fire department engine responds in about four minutes. The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) estimates that a one-minute improvement in response time by simply having the specific location of a mobile call would save over 10,000 lives. That response information also includes knowing who lives in a town or city.

Duty of Care to All

One of the most important responsibilities for emergency managers, 9-1-1 teams, first responders and local government officials is providing duty of care to their communities. But they don’t always know where these residents live, or how many individuals who are most at risk and what additional assistance they may need when severe weather or a natural disaster strikes. Having this information will allow emergency management and public safety agencies better prepare these community members for an emergency, while they understand what resources they will need to allocate.

The definition of who’s at risk depends upon certain criteria.

The Department of Health and Human Services (DHS) states an at-risk individual is someone with “access and functional needs (temporary or permanent) that may interfere with their ability to access or receive medical care before, during or after a disaster or public health emergency.” The agency defines at-risk individuals as children, older adults, pregnant women and individuals experiencing homelessness or have chronic health conditions.

Individuals with access and functional needs may include seniors and people with physical, sensory, behavioral, mental health, intellectual, developmental and cognitive disabilities, according to the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). They may also have limited English language proficiency, and access to transportation and/or financial resources to prepare for, respond to and recover from an emergency.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) defines an individual in a vulnerable population as someone who requires constant supervision, has difficulty communicating and accessing medical care, and may need help maintaining independence or accessing transportation.

During natural disasters, people with disabilities and older adults are two to four times more likely to be seriously injured or die. Nearly 1 in 4 Americans have complex access requirements and functional needs and will possibly be impacted during severe weather or a natural disaster.

- Approximately 12 million people with access and functional needs didn’t have equal access to emergency- and disaster-related programs during Hurricanes Harvey, Irma and Maria

- Outage-related issues, including medical device failure, accounted for almost one-third of over 4,600 deaths three months following Hurricane Maria

- More than three-quarters of the 86 people who died during the Camp Fire wildfire were age 65 and older or had access and functional needs

So how do stakeholders stay engaged with residents about an event, whether it’s urgent or timely? Who will be responsible for reaching out to residents? Where can stakeholders track what actions key personnel are taking?

Here are some other questions departments and agencies need to consider:

- How do emergency managers, 9-1-1 teams, first responders and local government officials continually receive and share information about an ongoing incident?

- Is there a way to ensure all the necessary actions and tasks will be done in preparation for a hurricane or blizzard? Or after a tornado or a wildfire impacts a community?

- How can they ensure residents and others will be protected wherever they’re located?

- What kind of assistance will some community members need?

- Is there a way for stakeholders to know about these needs beforehand?

Protecting an entire community is a complex and challenging priority for emergency managers, 9-1-1 teams, first responders and local government officials. Having reliable tools and accurate information will help stakeholders implement their preparation and response plans when a severe weather or natural disaster event strikes a community. Administrators will know what tasks will need to be done, who will be responsible for these actions, and when these tasks are completed, so they will have a clear understanding of what’s happening as the response efforts during a hurricane, wildfire or other major event evolve.

How Crisis Management Can Help During the “Golden” Minutes

After a blizzard, hurricane, flood or other major event strikes a community, there is precious time to initiate and respond. This critical time is maybe only a few minutes, even seconds. What’s accomplished at the start of an emergency will likely determine the complexity of the response, the severity of the severe weather or natural disaster event, and the success of the emergency response efforts.

The term, “golden hour,” is defined when an injured patient has one hour from the time of the traumatic injury to receive critical care to prevent death.

Now this period, or “golden” minutes, is the window of time where getting help is critical to the community and circumstances on the ground become challenging. The clock starts ticking away and key personnel start to mobilize.

But how do key stakeholders know who will be responsible for specific actions, such as reaching out to at-risk residents? Where will they find alert templates? How do they ensure first responders have checklists and other reference materials before they arrive on scene? How do stakeholders know if all the tasks are completed so they can issue an all-clear alert?

A crisis management tool will allow key leaders to activate a certain scenario with assigned critical tasks to personnel across departments and agencies. The tool, which works with an integrated mass notification platform, will provide directions for tactical decisions, establish clear responsibilities, and bolster coordination within departments and between agencies. Tasks can also be reordered, as well as created instantaneously as an event evolves. Emergency managers, 9-1-1 teams and first responders, for example, will receive an alert to initiate an assigned task to them when a severe weather event or natural disaster threatens a community.

Here are some examples of tasks that might be initiated when a flash flood occurs:

- Verify location of flooding

- Confirm severity and impact to local area

- If severe and affects local area, send flash flood alert

- Initiate one-click conference bridge with leaders

- Search database for criteria on demographics or locations of community members who are more at risk

- Launch poll to check in about status of at-risk residents

- Send updates, if changes in severity

- Begin evacuation procedures

- Establish road closures in impacted region

- Send all-clear alert

The crisis management tool will also communicate critical information to emergency managers, 9-1-1 teams and first responders in real time. For example, emergency managers can gather responses and real-time locations about at-risk residents from a poll through voice calls, text messages and emails. Once this action is completed, emergency managers can update notes in the assigned task and inform first responders which residents may need additional assistance.

As the actions around a severe weather event or natural disaster change, the tool will send reminders to emergency managers, 9-1-1 telecommunicators and first responders when a task needs to be initiated.

Tasks will also be listed, show who they were assigned to, indicate the status of the tasks, and when they are finished. Administrators will have a detailed timeline, so they can track what actions were implemented and what activities were completed. The tool will also provide an area where administrators can store reference documents, such as a checklist for EMS personnel to refer to when they arrive on scene after a severe weather event.

The crisis management tool will also allow emergency managers and others to launch alerts to residents in seconds. In preparation, administrators can create preset templates, including the type of emergency, data, location and what actions residents need to take.

The mass notification platform itself will allow key stakeholders to send alerts in three clicks from a smartphone or a laptop in an office or in the field. The platform automatically connects to devices through Common Alerting Protocol (CAP), such as public address systems and sirens, to share information quickly.

Messages will be sent out simultaneously through text, email, voice calls, IPAWs, digital signature and desktop alerts — all through a single touch point. They can be sent out in the mode and language residents prefer. With multimodal messaging and the ability to create preset templates, there won’t be a delay or gap in notifying residents as soon as possible.

Departments and agencies will also be able to communicate internally, so they’ll have the most current information to respond to these events and strengthen their collaboration and response efforts.

Administrators will be able to send out an unlimited amount of emergency messages to an unlimited amount of recipients, ensuring departments and agencies can scale up when severe weather or a natural disaster impacts a community.

Other tools that would assist emergency managers, 9-1-1 teams, first responders and local government officials include:

- Online emergency preparedness registry will offer an in-depth view of community members, such as medications, transportation needs and other details. The registry’s interactive web-based map interface will enable administrators to develop search criteria by demographics or location to focus on a group or segment in need of assistance.

- Text to opt-in feature provides residents, visitors and tourists with a way to sign up for alerts by texting a unique keyword to a short code. Keywords can change and administrators will be able to reuse for other situations.

- 9-1-1 integration provides 9-1-1 teams with critical details during an emergency, including the type, location, key contact information and facility layout, when the platform’s mobile app is activated. Emergency personnel will have a more detailed view of a building’s interior, including locked doors and access points, through geo-referenced floor plans. Telecommunicators can continue to provide information and send messages to on-site contacts as an incident unfolds.

- CAD data sharing increases situational awareness across jurisdictions, allowing emergency personnel to collaborate more effectively and improve mutual aid coordination. It automates critical notifications to key stakeholders, while reducing time transferring calls and sharing information.