La nature de l’intervention des services d’urgence 911 évolue en raison de l’ET3

Since the passage of the Medicare Improvements for Patients and Providers Act in 2008, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) has embarked on a value-based approach to providing better care for individuals and better health for populations at a lower cost by reimbursing providers based on the quality, rather than the quantity, of care they give to patients.

Historically, CMS’ value-based programs have mostly benefitted healthcare providers that have – for example – reduced rates of hospital readmissions and hospital-acquired conditions, or exceeded quality of care standards. However, in 2019, CMS launched the Emergency Triage, Treat, and Transport (ET3) program that aims to lower costs by reducing avoidable 911 ambulance transports to emergency departments and unnecessary hospitalizations following 911 transports.

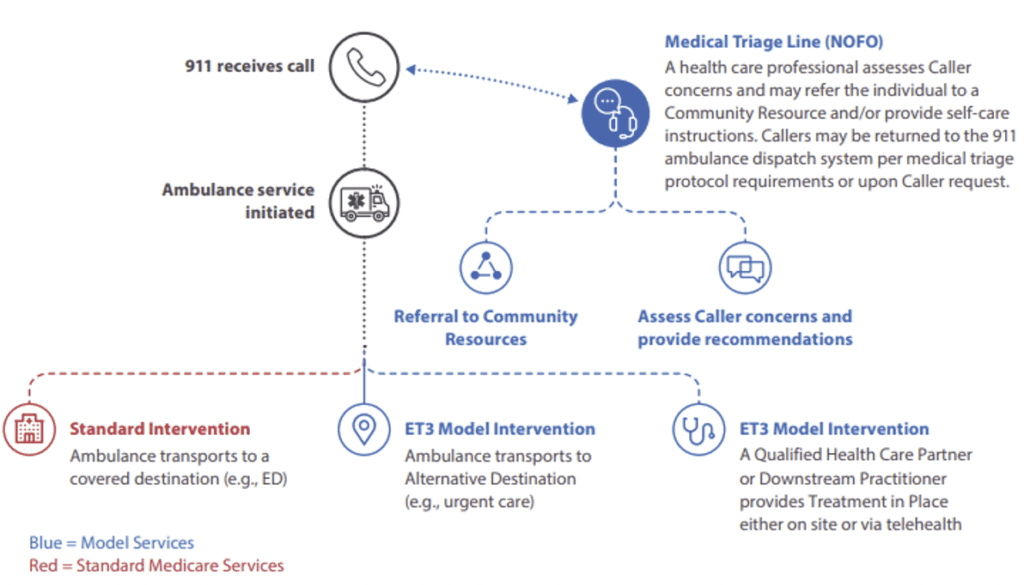

As the program applies to services most often operated by public safety agencies rather than healthcare providers (i.e., ambulance services, PSAP services, and state-run FLEX services), ET3 represents a departure from previous CMS value-based programs. The program is also a little more complicated than previous CMS programs inasmuch as the ET3 model consists of three “interventions” which can be connected to each other, but in many cases won’t be.

The Background to the ET3 Program

In the past, CMS only reimbursed ambulance services when individuals were transported to an emergency department (ED), critical access hospital, skilled nursing facility, or dialysis center. Consequently, the majority of ambulance transports were to hospital EDs – even when a lower-acuity medical facility would have been more appropriate for the individual’s condition – because transports to lower-acuity medical facilities were not reimbursed.

This had the effect of congesting hospital EDs with patients who could have treated much quicker, more appropriately, and at a lower cost elsewhere. Furthermore, in many cases, patients presenting at hospital EDs were unnecessarily admitted into acute inpatient care. This had the consequence of delaying treatments for patients with life-threatening conditions (i.e., heart attacks, strokes, etc.) – potentially negatively affecting their outcomes.

Since the launch of the ET3 program, participating ambulance services can now transport individuals calling 911 to “alternative destination partners” (i.e., physicians’ office, behavioral health center, etc.), provided the alternative destination partner is located within their “model region” and complies with the requirements of the ET3 model – typically that a medical service is available 24/7 or that, when combined with another partner in the same category, a 24/7 service is available.

Interventions 1, 2, and 3 Explained

Intervention 1 relates to the transport of an individual to either a hospital ED (which remains an option depending on the nature of the individual’s condition) or to an alternative destination partner. The decision where to transport an individual to can be made by EMS first responders on arrival at the scene, following Intervention 2, or on the guidance of Intervention 3 personnel. However, the individual retains the right to request transport to a hospital ED.

Intervention 2 gives EMS first responders the option to provide “Treatment in Place” – the treatment being provided by an on-site healthcare professional or via a telehealth service. The telehealth service can be provided by either the hospital to which the individual would have been transported or an alternative destination partner; and, if transport is no longer required once treatment has been administered, the ambulance service still gets reimbursed by Medicare.

Intervention 3 is a triage service in which 911 calls are transferred to a healthcare professional for an assessment of the caller’s needs. The healthcare professional can provide recommendations, refer the caller to more appropriate non-emergency services, or return the call to PSAP to dispatch an ambulance. Even though the call is returned to PSAP, the healthcare professional may still remain involved in the operation by advising first responders or conducting a telehealth consultation.

ET3 Gets Off to a Stuttering Start

The ET3 program was scheduled to start in early 2020 and run initially for a five-year period. Then the COVID-19 pandemic started and, in order to reduce the pressure on acute treatment hospitals, Intervention 1 was opened up to any ambulance service and any alternative destination partner irrespective of whether they met the ET3 model requirements or not. As the pandemic eases, the program will be scaled back to participating services only so it can be evaluated properly.

Similarly, the planned start of Intervention 2 was interrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic, and in March 2020, CMS vastly expanded the range of remote telehealth services available to Medicare beneficiaries in order to reduce the risk of exposure to COVID-19 for both patients and healthcare providers. This section of the ET3 model officially restarted on 1st January 2021.

With the COVID-19 pandemic ongoing, the start of Intervention 3 has been put back to later this year to given public safety agencies an opportunity to take advantage of a Notice of Funding Opportunity. Due to the delayed start of Intervention 3, the evaluation period will be just two years – although there is already plenty of evidence to demonstrate the value of having a healthcare professional triage 911 EMS calls, and evidence to suggest patients are becoming accustomed to being triaged.

How to Accelerate EMS Responses under ET3

Although the motives behind ET3 are excellent, there potential exists for delays to occur under the ET3 model due to first responders having little information about the individual, and healthcare professionals conducting telehealth consultations or triages having no knowledge of the individual’s past medical history. However, this issue is easy to resolve in CMS regions that support Smart911.

Smart911 is a free-to-use service that enables individuals to create safety profiles. The safety profiles can contain whatever information the individual chooses to disclose about past medical history, treating physicians, and medication, and the profiles are immediately available to first responders and PSAPs centers when a call is made to 911 from a phone number registered on the safety profile.

With this nature of information instantly available, first responders and healthcare professionals may be able to identify whether the individual is likely to have an adverse reaction to a particular treatment, if they have recently been treated by an alternative destination partner or community resource, or if there are issues that might influence to which destination the individual is taken.

In addition to accelerating the decision-making process, access to Smart911 ensures that, whenever possible, individuals are treated much quicker, more appropriately, and at a lower cost than if they had been transported to a hospital ED. Therefore, if you would like to access Smart911 in your jurisdiction, do not hesitate to get in touch with our team of public safety experts.